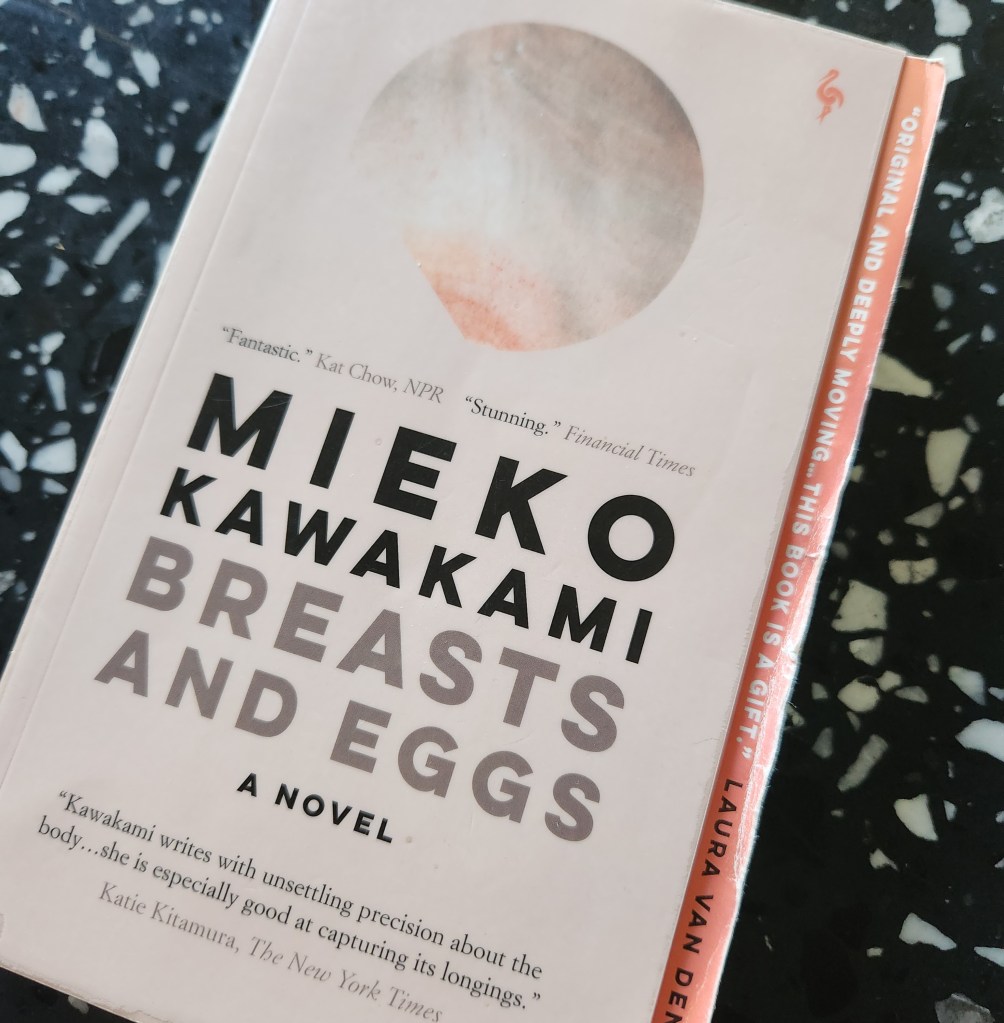

I decided to go ahead and read Heaven by Mieko Kawakami this summer while I was at it, and, wow, this is a heavy, but, of course, excellent book. It is such a departure from the much more distanced and gentler narrative in Breasts and Eggs, which I also read and wrote about a few weeks ago.

I’m not sure how I missed this, but there is a heavy portrayal of bullying in Heaven, and I don’t think that’s a spoiler, but I do think it actually does need kind of a big “trigger warning” splashed across the front of this book because it.is.intense.

However difficult this book may be, it is excellent, as Kawakami is proving herself (to me) to be an excellent writer–excellent pacing, character development, and a deep emotional landscape.

As an aside, this book is also much shorter than Breasts and Eggs, but my copy also included an excerpt of Breasts and Eggs at the end, and I’m not quite sure why this choice is being made because the current version available of Breasts and Eggs is also an elongated version of the original, but I just wanted to add here that this length of book–just Heaven–is a great length, and I think Kawakami works really well within this frame.