I just finished Men Explain Things to Me by Rebecca Solnit over the course of a few evenings. It’s a *heavy* read, but it’s composed of short, manageable essays. The first most noticeable thing about this book is that it is not funny. There is absolutely nothing funny or lighthearted about it, and that was a surprise. The title is sort of funny, and alludes to “mansplaining,” which is terrible and indicative of larger social issues surrounding gender, but it’s also sort of funny. The title is not a good indication of the book.

Solnit is unrelenting in her depiction of the “longest war,” a war on women. Reading it was overwhelming—a reminder of the violence and disdain lobbed at women by our society. The statistics were staggering. Having heterosexual relationships with men seemed increasingly fraught for both genders. I was left wondering how we navigate these weird power dynamics in our most personal relationships. I felt overwhelmed by the violence. I felt overwhelmed by the reminders of the constraints I face each day as a woman.

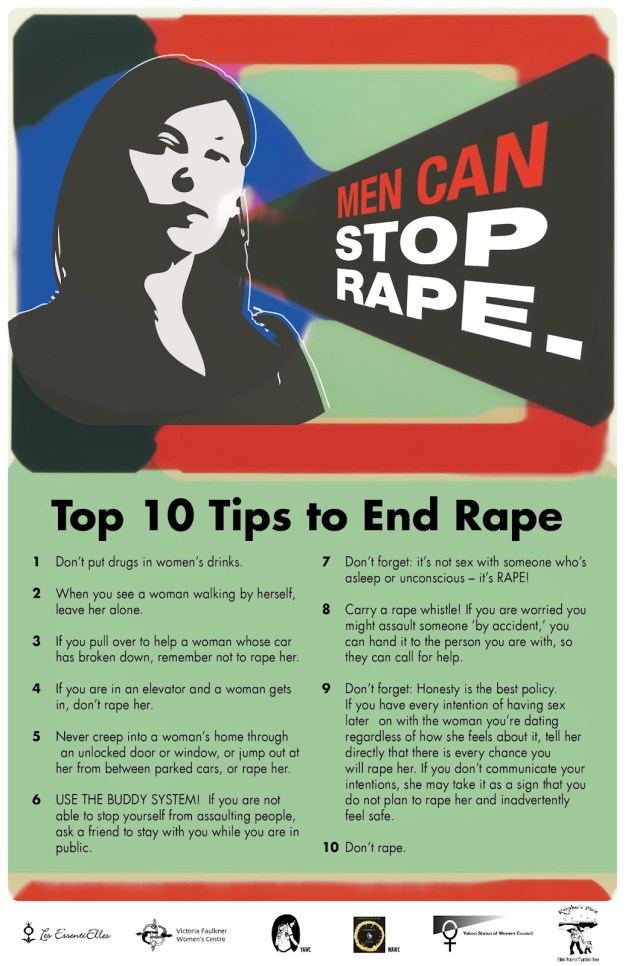

For example, each day before dark, I try to accomplish all tasks that require me to walk any distance alone or through a parking lot. Every day, I, mostly subconsciously at this point, plan my day with safety in mind. When I overtly think about these habits, it makes me sad that I live in such a violent world, and it makes me sad that safety has to be such an underlying factor in my daily decisions. Surely this has unknown negative effects. Solnit writes, “My feminism waxed and waned, but the lack of freedom to move through the city for women hit me hard and personally at the end of my teens, when I came under constant attack in my urban environment and hardly anyway seemed to think that is was a civil rights issue” (128). Solnit argues for an emphasis on turning the lens on men and why they are so frequently the perpetrators of violence, opposed to giving women the sole responsibility of preventing violence. This “Top 10 Tip to Avoid Rape” meme has made the rounds and points out the profound role that men (obviously) play in “rape culture.”

Like Solnit, I wonder why these problems are not viewed as a deeper crisis and as a civil rights issue. In recent years, I have felt a real personal fear as politicians have made absolutely horrifying, and often scientifically inaccurate, claims about women’s bodies. As the Hobby Lobbys and various right wingers argue about what I can and cannot do with my own body, for the first time, it has felt very personal and very stifling.

Of course, the reaction to these issues is often, yes, but “not all men.” And, Solnit carefully dedicates sections of each chapter, writing “not all men, but…” This is unfortunate. We can’t just talk about this issue without spending a lot of time reassuring men and women that not all men are bad. In so many ways it seems like this reassurance is also indicative of the problem. It’s a problem that we literally can’t even talk about women’s issues without spending a good deal of time reassuring men and talking about men and turning the focus, even just briefly, back to men. On the other hand, they’re half the population, and they’re our partners, fathers, brothers, and friends, and so it makes sense that we can’t talk about women without spending some time also talking about men.

The book isn’t entirely matched thematically, and she delves into some literacy criticism, as a way to address the larger social problems that she unpacks earlier in the book. She wrote of a criticism that “does not put the critic against the text” (101). In her exchange with Susan Sontag, Solnit writes that “you don’t know if your actions are futile; that you don’t have the memory of the future” (93). This is in response to Sontag’s assertion that resistance is required, even if it is futile, and maybe it is always futile.

On Woolf, Solnit writes of a botanist that had “a knack for finding new species by getting lost in the jungle, by going beyond what he knew and how he know it, by letting experience be larger than his knowledge, by choosing reality rather than the plan” (96), and I love this idea so much. For living life, for finding new ideas, for creating art. I am such a planner and a researcher, and I love the idea of this kind of purposeful method (which, yes, requires planning and research). I love the idea of using this method as a means of discovery, rather than following what is known: “a compass by which to get lost” (106).

Of measurement and discovery, Solnit also writes about “the tyranny of the quantifiable,” which is “the way what can be measured almost always takes precedence over what cannot” (104-105). This has been a frustration for me lately. Working in bureaucracies, and within high education, too often means a singular focus on the quantifiable, on the assessable. When other ways of being or knowing are scoffed at as being dangerous, even life-threatening, we are limited by what we can do as dreamers, thinkers, creators, and teachers.

This book reads up so quickly and so powerfully that there’s really no reason not to read it. Afterward, you can spend some time thinking through what it all means for gender, relationships, and the way men and women exist in the world. I think I’ll even pick up her other book, Wanderlust because it is about walking and maybe other things too.